I recently met with the Head of Data Science at one of the largest media conglomerates and as often happens these days, evaluation and quality of AI Agents came up. One of the most important problems he has been trying to solve is how to evaluate the quality of AI agents, and once in production, how to monitor them. And he is not alone – this comes up consistently with most of my discussions with Enterprise AI leaders these days. And justifiably so, if we want these AI Agents to drive decisions and take actions that have financial, regulatory, and reputational consequences.

The good news is that we have been down this path earlier. In the pre-GenAI era, we had the notion of evaluation and monitoring the quality of AI/ML models that were key to enterprise adoption of AI/ML algorithms in business-critical workflows. Which is why I thought it worthwhile to start with the fundamental concept that has been the scaffolding for measuring the quality of AI models.

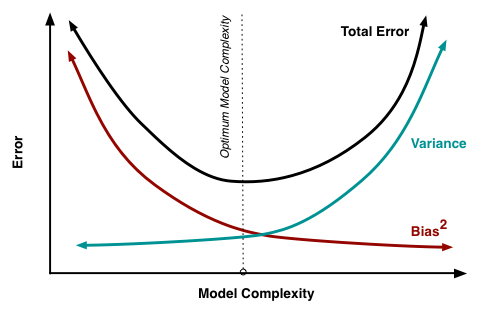

Bias vs. Variance

Bias-variance trade-off has been fundamental to the AI/ML model evaluation process. In umpteen models that I and my teams built over the last several years, this would be one of the key drivers to help us determine which model to promote to production. A particularly useful guideline is this excellent post by Scott Fortmann-Roe. See below for the visual from the blogpost that encapsulates the ‘Goldilocks’ stage that most model development teams aspire to achieve. And more often than not, it was always easier to grasp the idea of bias (i.e. a measure of how far off the model prediction is from the correct value), but variance (i.e. variability of model prediction for a given data point) was more nuanced and difficult to grasp. In the quest to minimize bias, there was often the quest to expand the feature set, often ending up with over-fitting the models. And this is not just academic – there are real-life consequences. For instance, fraud detection models with high bias can miss complex fraud patterns, while high variance can often flag normal behavior as fraud. In case of medical diagnosis, this could be even more consequential: high-bias might ignore nuanced symptoms, while high-variance might change predictions with minor patient data variations. It continues to be one of the most important goals to achieve in deploying all kinds of supervised/unsupervised ML models.

Fig1: The classical Bias-Variance trade-off

Neural networks and the Double Descent Curve

This paradigm started to change with neural networks as researchers observed an interesting phenomenon. To begin with, the models exhibit the classic behavior – as model complexity rises, test error falls, and then spikes as the model can barely fit the training data (similar to the classical overfitting view). However, surprisingly, as the model complexity increases further, test error decreases again, even when models have more parameters than data points and can pretty much memorize the training set. This is the ‘double descent curve’ (see below). All this would have ended up being an interesting research topic, until LLMs came along. The double descent phenomenon is evident in the performance improvement that we continue to see with LLMs even though they are heavily overparametrized (i.e. larger models perform better than smaller ones). And perhaps most importantly, this challenges the conventional bias-variance trade-off approach to overfitting and model scaling.

Fig2: Double-descent (Source: https://openai.com/index/deep-double-descent/)

So what?

How does all of this, if at all, matter to those of us who are interested in building Enterprise Agentic Systems? The trivial answer would be to go with the principle of ‘bigger models are better’. However, we are increasingly seeing that Enterprise Agentic Systems involve orchestrated networks of individually specialized agents (with their own models) interacting to achieve a complex goal. A good starting point would be to formalize an evaluation and ongoing monitoring approach to building these systems. The good news is that we have the tools to do this – let’s put them to work by designing the right strategies. Time to bring back the measurement and monitoring rigor that was instrumental in the widespread adoption of classical AI/ML in Enterprises. I plan to dive-deep into this over the next few weeks.

Further reading:

Databricks blog: Build, evaluate, and deploy GenAI with mlflow3.0

Understanding the Bias-Variance trade-off by Scott-Fortmann Roe: highly recommended

Deep Double descent from OpenAI. There are lots of other papers on this topic.

How do we evaluate Agentic AI Systems? Part-2

In the previous post, I had talked about the notion of the double descent in the Bias Variance trade-off and how that is shaping the notion of quality with LLMs. This post explores how all this translates to formalizing the notion of AI Quality, motivated by the need to go beyond ‘vibe quality’ for Agentic AI systems:

- What are some metrics for measuring quality for an Agentic System?

- How to define the System-level quality as the main criteria for Production deployment for an Agentic System?

Metrics for measuring quality

This obviously depends on the application. Broadly speaking, we see four Agentic patterns and here’s an attempt to define an AI quality process for each.

| Pattern-1Information Extraction Agent: Extract structured information from unstructured data | |

| Applications (Examples)This is a very common efficiency play across business processes:Extraction of data/features from documents (e.g. terms & conditions from contracts; line-items/payees from invoices etc.)Extraction and masking out sensitive information (e.g. PII data) from documents (e.g. contracts, invoices etc.) Extraction of insights from unstructured data (e.g. sentiment analysis from customer feedback, social media posts etc.)Quality is critical here given the financial and risk implications. | |

| Quality (Pre-production)Ground truth: A representative set of human annotated examples. Sampling strategy: It is important to get diverse ground truth examples, especially to avoid under-representation from edge cases and/or unbalanced datasets (e.g. sentiment analysis where data tends to be skewed towards negative feedback). I would highly recommend stratified sampling. Training vs. Test data: One interesting observation here – while with traditional Machine learning, a bulk of the data (sometimes over 80%) was used for training the models. Given that LLMs are already over-parametrized, there is an opportunity to actually flip this. In my experience, using <20% of the samples as part of the prompt, and retaining the bulk of the samples as hold-out data for actually testing the Agentic System should work well.Evaluation strategy: This is relatively straightforward, given that it is possible to compare the output from the Agentic system with the ‘expected values’ from the human annotated ground truth.Suggested quality metric: Information extraction Agents are similar to Classifiers, and hence useful to apply similar metrics:Precision: True Positives/ (True Positives + False Positives)Recall: True Positives/(True Positives + False Negatives)F-1 Score: harmonic mean of Precision and Recall. This is useful to balance out under representation. |

| Pattern-2RAG Agent: Extract structured information from unstructured data | |

| Applications (Examples)Q&A chatbots which can execute multi-turn conversations:Customer facing chatbots that can interact with customers on questions about products (e.g. policy choices for an insurer) and services (e.g. returns policies for a retailer)Internal chatbots that can automate some of the operational processes (e.g. HR helpdesk)Quality is tricky in these applications, given the subjective nature of the interactions. | |

| Quality (Pre-Production)Ground truth: A small set of examples typically used in the system prompt.Sampling strategy: It is critical to get diverse ground truth examples, especially to guide the chatbot on some of the less tangible aspects like tone, style etc. Training vs. Test data: The traditional model of training vs. test data does not apply here, since there is no ground truth to test the chatbot. Evaluation strategy: There needs to be a rigorous evaluation process. A recommended approach is to leverage a combination of AI judges and human SMEs to ‘grade’ the Agent’s responses based on a pre-defined set of metrics specific to the use-case (e.g. relevance, brand compliance etc.)Suggested quality metric: Some of you may have already seen the parallels with Binary classification, and the following might be useful:Accuracy: (True Positives + True Negatives)/ (Total)False Positive Rate: False Positives/(False Positives + True Negatives)Precision: True Positives/ (True Positives + False Positives)Recall: True Positives/(True Positives + False Negatives)F-1 Score: harmonic mean of Precision and Recall. As always, the actual combination of metrics would depend on the use-case and critically, the broad types of questions (e.g. informational vs. decision driven) |

| Pattern-3Text-2-Sql Agent: Natural language interface for Structured Data | |

| Applications (Examples)These are becoming extremely popular in Enterprise use-cases:Natural language interface for non-technical users to interact with data as a supplement to existing dashboards/reportsPart of a compound system where an Agent can invoke data from structured datasets as part of a decision chain.While Quality is critical, this is also one of the harder problems to solve. For instance, the Bird SQL benchmark is set against human (Data Engineers) accuracy of >92%, whereas the models are in the 75-78% range. Which makes it even more important to establish a Quality baseline for these systems. | |

| Quality (Pre-Production)Ground truth: A representative set of natural language questions with corresponding SQL pairs. Sampling strategy: It is important to get diverse ground truth examples, especially edge cases. The Bird SQL evaluation sets have some useful criteria to replicate real-life business scenarios (e.g. ‘dirty’ data, ambiguous joins etc.) Training vs. Test data: The traditional notion of ‘training’ doesn’t directly apply here, except in the case of some text-2-sql applications like Databricks Genie, which can ‘learn’ from sample SQL queries. Evaluation strategy: It is recommended to create benchmarks with the Ground Truth natural language questions and compare text-2-sql’s output with the output from the corresponding SQL queries.Suggested quality metric: A straightforward accuracy measure (% correct) that compares the text-2-sql’s output with the SQL query output. |

Putting it all together

We are now seeing the emergence of Composite Agentic Systems, which can autonomously plan and execute complex tasks in response to open-ended questions that cannot be deterministically translated to a pre-defined execution path. These involve an LLM with reasoning capabilities (‘Supervisor Agent’) with access to multiple tools and/or specialized agents (usually a combination of the above 3 patterns).

System-level Quality is of critical importance for deploying these systems in production to execute complex, multi-step tasks and/or provide meaningful decision support in Enterprise business workflows. As a recent study from MIT pointed out, less than 5% of these Agentic Systems have made it to Production and one of the main reasons is, as the report puts it, Verification Tax (“given that Generative AI models can be ‘confidently wrong’, even small inaccuracies necessitate constant human review and verification, erasing any potential time savings and thus the ROI”). The way to mitigate this is follow a rigorous, iterative process of ‘Improvement Engineering’ pre-production:

- Rigorous Quality tests for evaluating the individual components using the methods outlined above (Patterns 1-3) and iteratively improving on the design choices for the individual components. [Rough parallels to software unit testing]

- Overall System Testing that measures the overall accuracy (% correct) based on the output graded by a combination of AI judges and human SMEs. This has to be done repetitively at a system level after every improvement iteration at a component level.

- Over multiple improvement cycles, the overall system should continue to improve, until it reaches the pareto-optimal zone (i.e. asymptotically tends towards an Error % that is an inherent characteristic of the system).

- This then makes it possible to make a business decision: Does the error threshold meet the acceptable level of risk to deploy the Composite System in production for the efficiency gains?

AI Ops: Ongoing evaluation and monitoring

And finally, this is not a once-and-done process. As with classical ML models, Compound AI Systems need to follow the same AIOps processes with ongoing evaluation (e.g. grade the Agentic system’s performance using AI judges), monitoring (e.g. track metrics for the individual agents as well as the overall System for drift), and risk mitigation processes in place. It is clear that if we, as an industry, want to deliver the promise of Generative AI, we need to implement these Quality processes rigorously.

Leave a comment